Difficult Conversations

Moment of Truth:

Thriving cultures seek and share truth rather than avoid difficult conversations.

The Moment of Truth establishes and maintains reality, helps us navigate conflict, and invites participants to take ownership of their part in the mission. It guides leaders and organizations into prioritizing the seeking and sharing of truth.

Sharing truth is challenging and can create conflict. But avoiding it is worse – it leads to accepting false realities and pulls us away from our shared vision. Meaningful organizations seek and share truth as a regular practice.

Creating a culture that honors truth means that we have to measure small and measure often, making sure that we are where we think we are.

When should we use the Moment of Truth?

A Moment of Truth takes place when:

– Someone’s performance is not aligning with expectations (Freedom V)

– An individual doesn’t clearly understand our HERE

– An individual doesn’t clearly understand our THERE

Three ways to share truth

Me-to-Me: You share truth with yourself when you discover, learn, and contemplate one’s own life and experience. One example of me-to-me truth sharing is recognizing when you are in the Victim Circle. Another is owning the three things you can control.

Others-to-Me: Others often share truth with us by confronting us with “blind spots.” They can also expand our capacity for truth by sharing their experience and perspective.

Me-to-Others: We share truth with those around us by communicating the truth with grace.

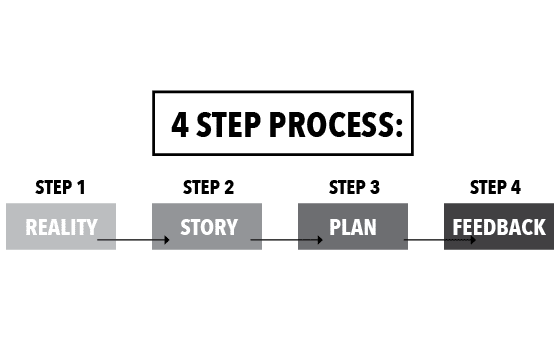

The moment of truth is a four step process:

Step one: Acknowledge Reality

Begin your conversation with yes or no, true or false questions. Understanding why something happened is important, but first you have to understand exactly what happened. We have to value truth enough to push to establish the facts first.

This might look like: Is the expectation that you begin your work day at 9:00 am? Did you start work at 9:00 am this morning?

Step two: Get the story

An individual’s performance might not live up to our expectations for many reasons. However, not all of these reasons are the root issue. Our goal should be to get to and understand the root cause.

Sometimes, the root issue can be a lack of clarity regarding expectations. When this is the case, as a leader, this is an opportunity to clarify and reestablish expectations and bring an end to the Moment of Truth. You should ask questions like “tell me more about…” “how?” or “what?”

Getting the story might look like: Why didn’t you make it in by 9:00 today? What is your morning routine? What other responsibilities do you have before work? How long does it take for you to get here?

Step three: Create a plan

A conversation won’t always be enough to fix whatever the root issue is. Come up with an action plan to help the individual meet expectations in the future.

You can help the individual learn how to establish healthy boundaries for themselves by creating SMART goals with them. This works because the structures we put in place demand specific behaviors. Good SMART goals create clear expectations and consequences.

As you work through the goal setting process, invite the individual to be a part of it. As much as is possible, you should decide on proper boundaries and consequences together (Freedom V). However, sometimes deciding on boundaries together will be inappropriate. Whatever you decide, make sure to put the plan in writing, since this will help you in step four.

Step four: Give feedback

Creating a feedback loop also creates accountability. We want to be intentional about following up with individuals, making sure the action plan is effective and driving the desired behavior. If the action plan is not driving desired behavior another MOT is necessary.

Three reasons why people don’t meet expectations

Roughly 95% of the time, neither personality or capability cause a mistake. SLY is a mental model that sets the stage for discovering the true cause of a mistake.

“S” stands for Structure (what we do and how we do it). Structure causes the problem 85% of the time.

“L” stands for Leadership (clarity and communication of expectations). Leadership causes the problem 10% of the time.

“Y” stands for You. Ask questions to help discover where the miss originates. Someone who is deliberately opposing the project causes the problem 5% of the time.

When conducting an MOT, assume the miss falls under either structure or leadership. Only when our structures and leadership are perfectly effective can we fully fault an individual for mistakes. This approach helps develop a shared ownership and informs the plan moving forward.

The four squares mental model

This model helps us understand why people accomplish or fail to accomplish their goals. The four squares are based on two categories: ability and motivation.

Ability: Does the individual have the knowledge and resources to achieve the expectation?

Motivation: Does the individual have the desire to accomplish the task?

The four combinations of motivation and ability are the four squares. They look like this:

1. Can and will: We want to be in this square. We only inhabit this square if the desired result is accomplished.

2. Can’t but wants to: This square describes a lack of ability NOT a lack of motivation. To address this square, your plan should include training and equipping.

3. Can but won’t: This square is purely a lack of motivation. Your plan to address this issue should include clarifying the connection between the assigned task and the THERE, including the values of the participant. If they don’t believe in the vision enough to commit to the tasks required to get there, they might be in the wrong organization.

4. Can’t and won’t: This is both a lack of motivation and ability. Your plan to address this problem should include both of the above adjustments.

How might pursuing truth lead to conflict? What are the repercussions of choosing your personal values rather than pursuing truth together in your organizations? How can you seek and share truth more effectively in your organization? Have you ever had a Moment of Truth with someone? How did it go? Why? If it went poorly, what could you do differently in the future?

Conflict Resolution

The Conflict Resolution Styles help us evaluate how we naturally react to conflict and move toward a mission-centered resolution. By itself, conflict is not a bad thing. It’s a neutral entity. How we respond determines whether it’s a net loss or gain.

Often, we refuse to share the truth because we fear conflict. However, we should not fear conflict, since conflict is a neutral entity, by itself neither good nor bad. If we resolve conflict well, it can and will benefit us. But if we resolve it poorly, it can hurt us.

When does conflict happen?

Conflict most often happens for three reasons:

- There is a lack of clarity of the THERE.

- There is uncertainty concerning the HERE

- In the Storming phase of the Mood Curve.

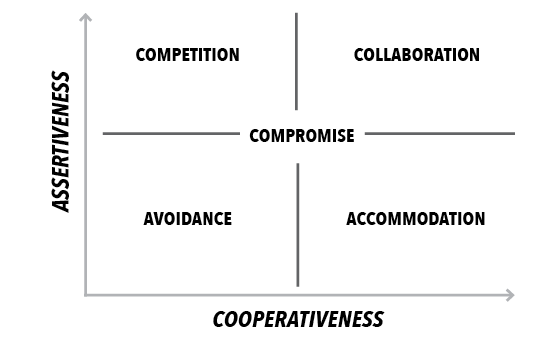

The five conflict resolution styles

Inevitably, conflict will arise. When it does, people will deal with it in vastly different ways. Here are five of them:

- Avoidance (The Bolter): The Bolter refuses to engage in conflict by not saying anything, shutting down, and leaving. They might say things like, “I’m not having this conversation right now.” This tendency can be valuable when emotions need to cool. But the danger lies in avoiding truth to preserve a false harmony.

- Accommodation (The Bower): The Bower lets the other party win, since they don’t think it’s worth it to continue to engage in conflict. They might say, “Alright, fine, let’s do it the way you suggest.” This tendency is valuable for small conflicts, but it can become dangerous when it leads to the silencing of underlying values, since this can cause a build up of passive aggression towards the involved parties.

- Compromise (The Broker): The Broker always tries to find a solution where both win a little and both lose a little. They might say, “Why don’t we try it your way this time and my way the next time?” This perspective can be very valuable when both perspectives of the truth are valid. However, it can be dangerous when it’s used as a clever way to avoid true resolution or when one perspective is not valid.

- Competition (The Boxer): The Boxer believes that there can only be one winner and fights to ensure that they are that one winner. This perspective can be valuable when a clear, definitive truth is at stake. But this is much rarer than we would like to admit. It quickly becomes dangerous when it’s centered on ME and sacrifices the truth for the sake of being right.

- Collaboration (The Blender): The Blender tries to find a solution that combines both perspectives. They might say, “Why don’t we take the best of both our ideas and try this together?” Unfortunately, this is not always possible. This approach becomes dangerous when time is wasted in an impossible situation, but it can be effective when it acknowledges diverse angles of truth and attempts to bring them together.

Each of the Conflict Resolution Styles have a time and a place. However, each can be dangerous if it is overused. We each have a preferred style, a factory setting. But we limit our effectiveness when we are not willing or able to engage in whichever style best serves the mission we are trying to accomplish.